Fixing education

The Philippine government is preparing to borrow $150 million (roughly P8.5 billion) from the World Bank (WB) to finance a series of projects aimed at improving public education. According to reports, these initiatives will run from 2025 to 2030, potentially benefiting over 21 million students from kindergarten to Grade 10. While any investment in education is welcome, a critical look at the numbers raises questions about the adequacy of this funding.

If we break down the P8.5 billion, this equates to approximately P425 per student over the five-year period. Considering the enormous challenges facing the education sector, this amount appears almost negligible. Yet, as modest as it may be, it is still better than nothing. The question, however, remains: can such a limited budget make a meaningful impact?

The most pressing challenge, as highlighted by the World Bank, is “learning poverty.” An alarming 91% of 10-year-olds in the Philippines cannot read and understand age-appropriate text. The country ranks near the bottom — 77 out of 81 countries — in math, reading, and science. These dire statistics point to a nationwide crisis, with overcrowded classrooms, poor teacher quality, and a lack of essential learning materials identified as primary causes.

It is crucial to acknowledge the systemic issues that have plagued Philippine education for decades. One of the most glaring problems is chronic underfunding. Despite constitutional mandates, public investment in education has been consistently insufficient. In 2019, education spending accounted for just 2.8% of the Gross National Product, far below the recommended 4% benchmark. This chronic underinvestment has created a ripple effect, impacting infrastructure, teacher salaries, and the availability of learning materials.

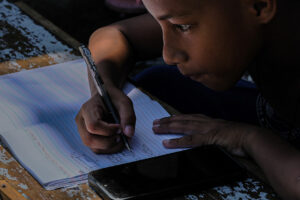

Many public schools, especially those in rural and remote areas, lack basic facilities like classrooms, libraries, and laboratories. Overcrowded classrooms are the norm, with one teacher often having to manage 40 or more students. This environment is hardly conducive to effective learning, and it is a reality that has persisted for at least half a century.

Another critical factor is the quality of teaching. Teacher education and professional development are areas in desperate need of attention. Higher passing rates in the Licensure Examination for Teachers, coupled with more opportunities for skill enhancement, can help address subpar teaching standards. We also need to ensure that our educators are well-trained, motivated, and equipped to adopt modern teaching methods.

Moreover, the curriculum itself may need a complete overhaul. The current system seems to place emphasis on rote memorization, rather than developing critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity. This is evident in our students’ poor performance in international assessments in reading, mathematics, and science. Many students know mathematical formulas but struggle to apply them in real-world scenarios or word problems.

Education inequality is another formidable challenge. In a country where poverty is pervasive, children from economically disadvantaged families often find themselves left behind. Geographic isolation further compounds the problem, limiting access to quality education, particularly in rural and conflict-affected areas. The urban poor face similar hurdles, with many parents unable to prioritize education when daily survival is a struggle.

It is easy to prescribe solutions like increasing the national budget for education or reforming the curriculum. However, these are far easier said than done. A large portion of the national budget is already tied up in debt servicing, limiting the government’s ability to allocate more resources to education. Nonetheless, a strategic increase in investment is crucial. Funds must be channeled effectively to improve infrastructure, provide adequate learning materials, and enhance teacher training.

Curriculum reform should be more than just an academic exercise. The new curriculum must prepare students for both local and global demands. As the Philippines is a major exporter of labor, our education system must equip students with skills that are relevant in a rapidly evolving global economy. Critical thinking, creativity, and practical problem-solving must be prioritized to prepare students for the future.

Improving teacher quality is equally important. The Department of Education (DepEd) must collaborate with the private sector to develop comprehensive professional development programs. These should not be one-off workshops but continuous learning initiatives that keep teachers updated on best practices. However, resistance to change is a real challenge. Many educators are reluctant to acknowledge the need for self-improvement, and breaking down this resistance will require concerted effort, possibly through mandatory continuing education.

No education reform will be complete without addressing the socioeconomic barriers that keep children out of school. The government must invest in targeted support for disadvantaged students. This could include scholarships, meal programs, and transportation subsidies. However, financial assistance should not be a blanket approach. It needs to be carefully targeted to maximize impact, ensuring that students with the potential to benefit most are prioritized.

And last but not least, while the government and educators play significant roles, parents are also key players in this equation. A holistic approach to education reform must involve parents as active partners in their children’s learning journey. Parental involvement can make a significant difference, especially in instilling the value of education and encouraging children to stay in school and strive for academic excellence. Simple acts, such as reading with children at home or reinforcing what they learn in school, can have a profound impact.

In countries like Singapore and Japan, the importance of parental involvement is well recognized. These nations have robust education systems, but they also have cultures that place a high value on education and parental engagement. While we cannot replicate their models wholesale, there are valuable lessons to be learned. For instance, promoting a culture that emphasizes education as a pathway to improving one’s quality of life can inspire students to aim higher and do better in school.

Obviously, we need more funding, better infrastructure, and highly skilled teachers. But we also need a curriculum that prepares students for real-world challenges. And perhaps most important, we need parents to step up and be active participants in their children’s education. Education is a shared responsibility, and everyone — government, teachers, parents, and society at large — has a role to play.

Marvin Tort is a former managing editor of BusinessWorld, and a former chairman of the Philippine Press Council