Twists and turns in the Year of the Snake

(This is an edited version of the speech given by the author during the Institute of Corporate Directors’ induction on Feb. 14.)

TODAY I will share my outlook on the Philippine economy — a topic that aligns with my present responsibilities. I chose the title “Twists and Turns in the Year of the Snake.” The snake seemed to be the apt Chinese astrological animal at this time of unprecedented uncertainty, where we can be unsuspectingly fatally bitten, or, to mix metaphors, be tempted by forbidden fruit with tragic consequences. (Although, as the old joke goes, if Adam and Eve were Chinese, they would have eaten the snake instead!).

On a more serious note, I must also ask for your understanding. I cannot be as open as I used to be when I did briefings as private global analyst for GlobalSource Partners.

My talk will be in three parts. First a situationer on the Philippine economy, how it is doing, what are the sources of strength. Second, what are the uncertainties and risks that we need to keep an eye on. Finally, what is the role of corporate governance in ensuring that our companies are resilient, agile and nimble, fast strong and tough, in the face of these threats and challenges.

The Year of the Snake is off to an interesting start. Global markets are grappling with the possible repercussions of the ongoing geopolitical fragmentation. Much has already unfolded this early in 2025, and there are bound to be more twists and turns in the months ahead.

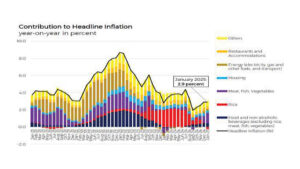

In this environment, the Monetary Board decided yesterday to keep policy rates steady. This followed three consecutive rate cuts beginning August last year that reduced the key overnight RRP rate from 6.50% to 5.75%. The cuts reflect the country’s progress in lowering inflation. Headline inflation decreased from a peak of 8.7% in January 2023 to 2.9% in January this year. Measures of underlying inflation have declined and our projections indicate we will be within target average inflation through 2026. Inflation expectations also remain within target.

Nonetheless, as I mentioned earlier, elevated policy uncertainty over the external environment warranted a pause in monetary policy easing at this juncture. The BSP (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas) is attentive to the risks to our inflation outlook, which are broadly balanced until 2026, and it remains to be seen how the current geoeconomic shifts will impact us.

Let me be clear that the BSP looks to continue its measured shift toward less restrictive monetary policy settings but it will remain data-dependent in deciding on the pace and timing of further reductions in the policy rate.

Although our primary focus is inflation, in calibrating the monetary stance we also take into account the impact on the real and financial sectors to ensure that the country remains resilient on a wide front.

After a brief post-pandemic spike, economic growth has slowed to an average of 5.6% in the last two years compared with the 6% to 7% growth clip pre-pandemic. Nevertheless, we expect GDP growth to breach 6% this year and next. Disinflation and a less restrictive monetary policy stance, including the impact of prior monetary policy adjustments on the economy, form part of the growth story. The main part of our growth story will continue to be driven by OFW (overseas Filipino workers) remittances, BPO (business process outsourcing) revenues and government’s infrastructure program, which has been kept at 5% to 6% of GDP. The growth story will be supported further by government’s commitment to fiscal consolidation, credible monetary policy, and healthy international reserves that serve as a reliable backstop against external shocks. Note also that our sovereign rating has a good chance of getting an upgrade based on S&P’s positive outlook on credit.

These positive macro developments will also contribute to financial sector stability. The banking sector has maintained solid performance, demonstrated by a continued uptrend in assets, loans, deposits, and earnings, along with reasonable provisions for non-performing loans (NPL). As we gradually dial back monetary policy restrictions, we see that further reductions in the reserve requirement ratio will appropriately support our continuing shift towards more market-based monetary operations. We want to minimize financial system distortions in the form of high intermediation costs and transaction fees so that banks can more efficiently channel their funds towards productive loans and investments. Future adjustments in reserve requirement ratio to bring the Philippine’s reserve requirement ratio in line with its peers in the region will ultimately enhance monetary policy transmission.

I hope I have not made it sound like that all is well with the economy.

As we all know, the pandemic has left a mark on the economy with outputs in some sectors, notably real estate and some manufacturing industries, still below their pre-pandemic levels. Investments as a share of GDP are lower than they were pre-pandemic despite higher public construction under government’s Build Better More infrastructure program. This has contributed to weaker labor productivity and lower potential economic growth rate. Public debt as a share of GDP is 20 percentage points higher than it was pre-pandemic, highlighting the need to rebuild fiscal buffers. Poorer education outcomes as well as skills shortage are also very much part of our pandemic scars and present medium-term challenges to growth, including in the IT-BPM (Information Technology and Business Process Management) industry.

We also emerged from the pandemic having to face unprecedented geopolitical turmoil. The Russia-Ukraine war, the war in Gaza, and now Donald Trump in the White House. The landscape of external risks arising from policy uncertainty, particularly from Trump 2.0, calls for increased vigilance against potential supply shocks and a global growth slowdown. Perhaps the big question on everyone’s minds at the moment is just how far this trade war could go and how much of a blow this could be to the global economy and the Philippines. Yesterday, our economic research group showed us indices of trade uncertainty and policy uncertainty, both of which spiked, graphically a vertical line up.

Although nobody really knows at this point how far the trade war will go, I think we can learn from the experience during the first Trump administration when the US-China trade conflict led to tariffs on over $500 billion worth of goods in both economies.

• First, between September 2018 and December 2019, total exports from the ASEAN+3 region contracted significantly in value, after growing previously at an average rate of 10%. The Philippines was largely insulated from trade tensions during this time, reflecting its low participation in global trade and value chains. Today, the Philippines’ trade surplus with the US is relatively small, which makes it less likely to face targeted US tariffs.

• Second, despite the Philippine’s close trade ties with the US, the country did not benefit much from the resulting relocation of firms’ production bases unlike, for example, Vietnam and Mexico. The fear this time is that the anticipated higher tariffs on other countries, particularly China, could lead to inefficient fragmentation of global supply chains and further dampen global trade flows. With the Philippine’s friendlier ties with the US under the current administration, will it be able to strengthen trade relations with the US through a bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA) and other sectoral agreements?

• Third is on trade in services. Seventy percent of the market of the country’s IT-BPM industry is in North America (predominantly the US). Under Trump’s previous term, growth in Philippine BPO earnings slowed sharply to 2.5% in 2017 and 3.9% in 2018, from 12.3% in 2016. Given Trump’s protectionist bent, there appear to be plans by US firms offshore to move operations closer to the US, either through reshoring or relocating to politically stable or geographically convenient countries. This adds another layer of complication to an industry that is being disrupted by the emergence of generative artificial intelligence. I have talked with industry insiders who seem fairly confident of sustaining growth in line with the overall economy. Their optimism that the Philippines can adapt hinges on moving up the value chain with further AI integration supporting growth and catering to increasing demand in healthcare outsourcing. Expanding markets in Europe and Asia-Pacific would also help in partially offsetting the possible decline in US outsourcing demand.

On the local front, we only need to open the front pages of the newspapers to appreciate the looming risks that may impact the economy, not just this year but beyond. Though 2025 is only holding senatorial and local elections, it is shaping up to be an existential contest among the protagonists, with profound consequences on our country’s medium term domestic and foreign policy (including on big power conflict) and our future.

Now to the subject close to our hearts as fellow advocates of good corporate governance. At the risk of bringing coal to Newcastle, let me share some of my thoughts on the role of the board and good corporate governance in the face of such heightened VUCA (volatility, uncertainty complexity and ambiguity) the likes of which we have not seen since the concept was introduced in the US Army War College in 1987.

I will give some current thoughts and draw from a column I wrote in June 2017 when I was an independent director in a major bank. The column, “Corporate Governance in the Digital Age,” excerpted remarks I gave to a forum organized by the BSP and IFC on corporate governance for banks. While the landscape has evolved since then, I believe the core principles remain just as relevant today.

1) Board Composition. Governance starts at the top. Good corporate governance is ultimately the responsibility of the board. As is often rightly said — companies do not fail, boards do. It starts with having the right men and women in the board with rich and diverse backgrounds. Diverse in the terms of gender, age, cultural background, education, professional experience, length of service.

A diverse board is not just about representation. It is a matter of resilience. The more diverse perspectives we have in scanning the horizon, the better prepared we are for what comes next. When leaders from different backgrounds, disciplines, and experiences come together, they collectively bring unique insights that help organizations think through complex risks, challenge assumptions, and seize opportunities. In an age of rapid disruption — from trade policy shifts to AI driven transformation — having a boardroom that mirrors the complexities of the world is not just valuable; it is essential.

As Darwin famously observed, the species that survives is the one that is best able to adapt and adjust to the changing environment in which it finds itself. The same holds true for corporations. Those with diverse, dynamic leadership are the ones that will endure.

Listen to Darwin, ignore Donald.

2) Culture. Governance is more than compliance. My 2017 column mentioned that in the institution I was with, governance went beyond formal rules. “For us it is all about imbibing and nurturing a culture of integrity, fairness, accountability and transparency cascaded from the Board, its management, and to all our employees.”

I am sure here in the ICD you are making progress towards nurturing such a culture in all the companies you monitor, as well as in your own practices.

Culture determines behavior. Without the right governance culture, even the best policies and structures will fall short.

We need only look at past crises to see why this matters. Take the Global Financial Crisis — a textbook case of failed governance, where conflicts of interest went unchecked. Credit rating agencies, for example, were paid by the same companies they rated, even advising them on securitization structures that will result in good rating scores. That lack of independence and integrity had catastrophic consequences. The lesson? Strong governance is not just about ticking the boxes, or even following the letter of the rules. It is about embedding the right values.

3) Risk Management. In that same column, I quoted BSP Governor Amando Tetangco, who said that “risk management is at the heart of corporate governance for banks.” That remains true not just for banks, but for all businesses. Risk today comes in many forms — geopolitical uncertainty, cyberthreats, regulatory shifts, financial market volatility, and even reputational risks amplified by social media. Given the unprecedented risks all around, we all need to upgrade our risks management systems commensurate to the heightened threats.

We are all navigating an era of economic shifts, geopolitical tensions, and rapid technological advancements. Businesses that embrace good corporate governance — not just as a compliance exercise, but as a strategic imperative— will be the ones that remain resilient, adaptable and competitive. Good governance is not just about rules and regulations; it is about building organizations that can anticipate and respond effectively to change. It is about ensuring that decision-making is informed, transparent, and accountable.

As corporate leaders, policymakers, and advocates of good governance, we have a responsibility to uphold these principles. The choices we make today — who we bring to the table, how we structure our decision-making, and how we anticipate risks — will determine our ability to navigate the twists and turns ahead. I highly commend and congratulate ICD, its Founder, leaders past and present for being at the forefront of corporate governance reforms for the past two decades!

The Year of the Snake will surely bring its share of surprises. But with strong governance, diverse leadership, and a steadfast commitment to resilience, we can ensure that Philippine businesses remain agile, competitive, and ready for the future — no matter what it holds.

Romeo L. Bernardo is a member of the Monetary Board.