Five things to consider when voting: The health and nutrition edition

The Philippines 2025 midterm elections will be held on May 12. On that day, Filipinos will elect senators, district representatives, party-list representatives, and local government officials. With tens of thousands of candidates vying for 18,320 elective positions to be voted for this year, voters are challenged to choose the right candidates.

The recent survey of the Social Weather Stations shows that a top issue among voters is health. Ninety percent of the voters “will vote for a candidate who will advocate… strengthening the healthcare system.”

The politicians should be aware of this. To garner votes, politicians appeal to the aspirations — or desperation — of Filipinos for freedom from poverty and destitution. This is why politicians make promises on giving prosperity by providing social services and distributing taxpayer-funded ayuda (assistance).

However, band-aid solutions do not eradicate poverty. Poverty must be addressed in all its dimensions, including malnutrition that traps families in poverty. This situation breeds dependence on dole-outs that serve as vehicles for patronage politics.

Here are five things we should consider when choosing who to vote for in the midterm elections this May. Let’s call this the health and nutrition edition of who to vote for.

This is a challenge and a call to Filipinos to examine the candidates’ platforms, and for reelectionists, their track record in terms of lasting impact on the nation’s development.

1. Dapat may alam (someone knowledgeable): recognizing the triple burden of malnutrition.

The Philippines is facing a triple burden of malnutrition. Different forms of malnutrition, such as undernutrition, overnutrition, and micronutrient deficiency, afflict millions of Filipinos. Annually, the country loses a staggering P496 billion to malnutrition — or a daily loss of P1.36 billion.

Undernutrition may be acute (also known as wasting or being thin) or chronic (also known as stunting or being short for age). Wasting, stunting, and micronutrient deficiency may co-exist in a single individual.

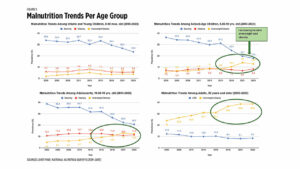

Across age groups, a common paradoxical trend is emerging: the slowly declining prevalence of undernutrition is being met with the rapidly rising incidence/prevalence of overnutrition. While we are gradually addressing stunting, wasting and vitamin- and mineral-deficient diets, we are faced with ballooning cases of an equally concerning form of malnutrition — an epidemic of overweight and obesity.

Amid this triple burden of malnutrition, children under five stand to be the most severely affected. This age group encompasses the first 1,000 days of life, from the point of conception until a child’s second birthday.

The first 1,000 days form a critical period of development, which, if compromised, may lead to irreversible injury and insult. Harsh early environments in the womb may manifest as low birth weight, and via “intrauterine programming,” as serious health problems later in life, e.g., the “metabolic syndrome,” an overlap syndrome of overweight/obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders.

The impact is not just over the lifetime of one child, but is intergenerational. Picture a pregnant teenager. She needs an adequate diet for her own growth, plus the needs of her developing fetus — and yet, she is likely subsisting on instant noodles, junk food, and soft drinks that are high in salt, trans fat, and sugars. She is probably consuming excess sugars and carbohydrates, but not enough building blocks — protein and healthy fats — for growth and development of her fetus’ organs, including the brain.

To make things worse, she may be consuming alcohol, vaping or smoking. A teenage adolescent is more likely to conceal her pregnancy and not seek prenatal care early. Without guidance and because of her unhealthy diet, she is at a higher risk of developing hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes, her pelvis may be narrow and thus if her baby is a big baby, she runs a higher risk of having to deliver via cesarean section. Her low birthweight offspring now becomes one of the future generations of nutritionally at-risk children.

We need more champions in government who will raise awareness about the triple burden of malnutrition, with a strong understanding of the importance and urgency of investing in the right nutrition, especially in the first 1,000 days of life.

2. Dapat may pakialam (someone who cares): Championing urgent and sustainable solutions

The country’s malnutrition problem is not a new topic. And yet we have seen minimal progress and are off-track in achieving our nutrition targets, especially in curbing overnutrition among all age groups.

We have been underinvesting in nutrition. Figure 2 illustrates the funds for nutrition-specific programs that make up an insignificant portion of the national budget, hardly even visible in the graph below.

Malnutrition fuels broader health crises — particularly the rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In 2024, Philippines Statistics Authority (PSA) data showed that NCDs remained as the leading causes of death among Filipinos, with ischemic heart disease being the top cause and diabetes ranking fourth. Annually, the country loses P756.5 billion to NCDs, according to the World Health Organization.

Our leaders should be proactive in crafting and implementing sound and sustainable solutions.

3. Hindi nagmumudmod ng ayuda (does not distribute assistance): Rejecting patronage politics that breeds pagmamakaawa (begging) and utang na loob (debt of gratitude), to allow citizens to claim their inalienable right to health.

NCDs are chronic and costly to treat, often leading to medical expenses that can last a lifetime.

According to PSA data on health spending, the Philippines spent P728 billion on NCDs alone. The largest portion (44.4%) came from the pockets of Filipino people. That is an estimated P323.2 billion worth of health expenditure — a sum equivalent to the entire national health budget for one fiscal year.

Hence, the Universal Health Care (UHC) Act established the role of the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (PhilHealth) as the key purchaser of health services.

This mandate is funded by premium contributions from PhilHealth members, along with earmarked revenues from sweetened beverage (SB) and tobacco taxation.

Even if out-of-pocket healthcare expenses remain high, the Department of Finance ordered the transfer of P89.9 billion of PhilHealth funds to the National Treasury in 2024. To make matters worse, Congress inflated the budget for the Medical Assistance to Indigents and Financially Incapacitated Patients (MAIFIP) program, a band-aid medical ayuda scheme which forces patients to beg for aid, rather than strengthen an institution that ensures dignified healthcare financing.

Enough with the utang na loob mentality that fuels the ayuda politics of traditional politicians or trapos. The healthcare assistance we receive is not a favor — it is funded by our taxes, paid with our hard-earned money.

4. Walang utang na loob na pagbabayaran (no debts to gratitude to be paid): Scrutinize candidates’ campaign backers and vote for those who cannot be bought.

Good governance rejects the scheme of trapos that breeds utang na loob. This applies not only to patronage-driven politics but also to the influence of campaign funders.

The danger of politicians being backed by industry players is that they will distort policies to favor the industry backers — evident early this year when the House railroaded House Bill 11360, branded by civil society as the “Sin Tax Sabotage Bill.” HB 11360 proposes to reduce excise taxes on tobacco. Its proponents, mainly identified with tobacco interests, make the false claim that lowering taxes will curb smuggling. The true beneficiaries of this bill reducing tobacco taxes, however, are tobacco companies, which stand to profit at the expense of public health.

The Sin Tax Reforms have significantly reduced smoking prevalence — from 28.3% of adults smoking in 2009 to 19.5% in 2021. The proposed “Sin Tax Sabotage Bill” threatens to reverse these gains — if passed, it is projected to result in almost 2 million new smokers by 2030, according to Action for Economic Reforms.

We must reject the pro-tobacco bill. Its passage can likewise lead to undermining sweetened beverage and alcohol taxes, the very taxes that fund UHC.

5. ’Yung may plano (someone with a plan):check for clear and concrete Local Nutrition Action Plans

Concretely, we ask: What are their programs, projects, and activities that serve the Local Nutrition Action Plan (LNAP)? Do they undertake participatory approaches, not merely tokenistic approaches?

On Election Day, consider voting for candidates who will champion health and nutrition. The five things to guide our vote — dapat may alam; dapat may pakialam; hindi nagmumudmod ng ayuda; walang utang na loob na pagbabayaran; ’yung may plano — apply not only to the vote for health and nutrition. They apply to how we must vote in general.

Ma. Dhelyn Dela Cruz and Rosheic Sims are researchers for the fiscal and health policy team of Action for Economic Reforms (AER). Maria Asuncion Silvestre, M.D. is a World Health Assembly Laureate (2023), recipient of the United Arab Emirates Health Foundation Prize, and the founding president of Kalusugan ng Mag-Ina (KMI).