Sleepless in Malacañang

Imagine inflation keeping President Bongbong Marcos awake at night. This much the President admitted last week in an interview with television journalists at Malacañang. Troubling him are the most pestering of farm products, such as onion and sugar, thanks to traders and hoarders.

He must have realized what is going on as he argued that “even if we bring tons of onions (to the market), the prices won’t go down tomorrow. It will pass through the system. It takes a little while, but it won’t be that long, this year.” Quite optimistic, but over time, he expected that “because we put onions and sugar in the market, somehow the supply will feed the demand, the prices will go down.”

The President should not worry about spending sleepless nights, for he is not alone.

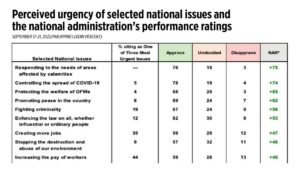

Of the 13 “perceived urgency of selected national issues,” Pulse Asia Research reported that 66% of survey respondents cited controlling inflation as the top urgent national concern. The survey was done in the middle of the President’s first six months in Malacañang and the results were released on Oct. 6. During that time, the issue of sugar imports and the subsequent sharp increase in sugar prices hogged the headlines and the headline inflation. Sugar is a key ingredient to many food products in the consumer price index, affecting both small and big food industries. This must have initiated the President’s waking hours at night.

Sleepless nights continued with the spike in white onion prices in local markets to as high as P400 per kilo in the early part of August last year. The President was advised by his appointed officials that bad governance was behind the problem. Logistical problems of storage were driven by what we may describe as territorial capture, as local government units attempted to exact tolls that were made even worse by various checkpoints by uniformed personnel.

But the President must have also been alerted in the last couple of days that the price of garlic has started to shoot up to P400 per kilo and it’s driven by farmers’ decision to shift to onions. Even as the Agriculture department insisted that “we don’t have a shortage of garlic,” in the same breath there was an admission that the Philippines today suffers from a “small supply of local garlic.” We have yet to establish the substitutability between local and imported garlic, but they must be close substitutes. It is possible the President’s sleepless nights are due also to some people around him who denied any shortage of the commodity while disclosing that we only produce a mere 4% of our garlic requirements.

Earlier, the Agriculture department itself expressed disbelief that even egg prices had escalated to as much as P10 a piece. Central Luzon was reportedly affected by bird flu that required the culling of about 1.8 million chickens. A shift of supply to southern and northern Luzon should increase logistical costs.

If tomatoes follow this series of commodity inflation, as what was experienced in India last year for several months, restaurants and households would have a hard time serving Filipino-style omelets. But the issue of inflation is beyond eggs, onions, and garlic.

It is also about its social consequences, intended or otherwise, and therefore it is at the heart of political governance.

If 66% of respondents of the Pulse Asia survey — the same survey that predicted the Marcos victory at the May 2022 polls — cited inflation as most serious and urgent issue, 44% of the respondents were also spot on considering the increase in workers’ pay as second priority. If prices are rising fast and furious, the immediate buffer is to adjust the people’s purchasing power. Their third priority is most logical and this is to create more jobs. Some 35% of the respondents were convinced that job creation could be a good mitigant. Many respondents succeeded in connecting these dots.

While the administration appears to have scored net positive approval for increasing the pay of workers — and this must be due to the cash payout and special adjustments in workers’ pay during the pandemic, as well as in job creation, thanks to the new industries of movers and home cooking and catering — it is important not to ignore the share of the undecided. They either had little information or were plain secretive about their true sentiment.

In the case of inflation control, the government scored a net disapproval of 11%. Some 42% of the respondents considered government efforts had failed and 31% approved of how inflation was managed. The undecided respondents were less than those who supported public measures against price stability measures.

The reason for the President’s sleepless nights has important implications on the dynamics of inflation. As the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) last year observed, the broadening price pressures may have caused households and firms to move out of the zone of “rational inattention.” Arguably, inflation may not have that much influence on their behavior, and instead pushed them to focus on just a few consumer items.

In the case of the Filipinos, they have precisely turned more attentive to price movements of, yes, rice, sugar, onions, garlic, and perhaps in the near future, tomatoes. It is possible that other items in the consumer basket are priced more reasonably but consumers have limited ability to consider all inflation developments in their own decision to consume or invest.

Based on this, one can expect households and firms to behave in a way that could protect their purchasing power, by demanding more pay, or profit, by selling high. This process could feed into higher inflation expectations. Demand for higher wages and price adjustments could only lead to inflation becoming even more entrenched.

All up, if these price trends of omelet ingredients continue and inflation expectations remain uncertain, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) may have to sustain its tightening mode much longer.

We have some clues.

Last week in Frankfurt, BSP Governor Philip Medalla assured the investment community that by the end of the third quarter or by the fourth quarter, inflation would be below 4%. Due to large base effects, inflation is expected to tip 2% in early 2024. His caveat was very revealing, if not too obvious. It’s impossible to rule out another supply shock, and the BSP was correct in anchoring its forecast on a successful resolution of agricultural shortages. This is a very strong assumption.

While it was good for the BSP to telegraph the direction of its policy stance, how long this could be sustained is a difficult task. If the Agriculture department remains in disarray, the prices of these omelet ingredients are bound to run away.

Moreover, the latest inflation footprint for January and its implications on one-year ahead forecast may justify sustained tightening. Two days ago, the BSP announced its projection for January at between 7.5-8.3% “due to a rise in power and water rates, and higher pump prices.” Utilities and energy are new variables in the equation. If this forecast holds, the January 2023 inflation would be the 10th straight month that price movements surpassed the 2-4% inflation target of government. In fact, the BSP’s optimism that the decline in LPG prices in January is good for inflation might be transitory. In fact, LPG prices already rose by over P120 per tank yesterday, and an 11-kg LPG tank would now cost over P1,000.

The IMF resident representative Ragnar Gudmundson two days ago also expected a breach in the inflation target for this year. More BSP interest rate tightening may be in order, according to him.

What is more revealing is the IMF’s estimate of what needs to be done at this point. “In the case of the Philippines, we estimate that the neutral real rate, which is the net of inflation interest rate where monetary policy is neither contractionary nor expansionary stands between 1% and 2%.”

If inflation for this year is 4.5% for BSP and 4.7% for IMF, given its current policy rate of 5.5%, then the BSP will have to continue jacking up by a maximum of around 100 basis points to 6.5%. Pray that the BSP’s ammunition would remain adequate should the Maharlika bill be rushed into law.

President Marcos should brace himself for more sleepless nights.

Diwa C. Guinigundo is the former deputy governor for the Monetary and Economics Sector, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). He served the BSP for 41 years. In 2001-2003, he was alternate executive director at the International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC. He is the senior pastor of the Fullness of Christ International Ministries in Mandaluyong.