Addressing the challenge of agricultural development

(Part 1)

As if to dare President Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. to exert even greater effort in meeting his greatest challenge, which is that of improving the productivity of the agricultural sector, agricultural output contracted further during the quarter in which he was sworn in as President and in which he designated himself as the Secretary of Agriculture.

Data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) showed that the value of production in agriculture and fisheries at constant 2018 prices declined 0.6% in the April to June 2022 period, worsening from the 0.3% contraction in the first quarter. The President knows that increasing agricultural productivity is not going to be a walk in the park. That is why one of the very first advisory groups from the private sector that he convoked was in food security, composed of some of the most experienced entrepreneurs in the field of agribusiness gathered by his private sector adviser, Sabine Aboitiz.

The President is fortunate that the outgoing Secretary of Agriculture, William Dar, led a group of experts from his own Department and from outside experts (some of them former Secretaries of Agriculture) to come out with a Transition Report filled with recommendations and specific policy targets and solutions towards long-term visions of food security and food sovereignty, while at the same time emphasizing urgent action points, especially in the context of a looming food crisis worldwide brought about by the Russia-Ukraine war. This document should be closely studied, not only by the members of the Cabinet of the present Administration but also by all those in government, business, and civil society who want to make their contribution to solving the problem of agricultural underdevelopment. To do something about the low productivity of farmers and fisherfolks is to directly address the problem of mass poverty since three-fourths of those who fall below the poverty line in the Philippines (now estimated at 18.1% of the total population of about 112 million) are in the rural areas.

As every effort to address an economic problem should, the Report starts with a situational analysis. Over the period 2001 to 2021 (one generation), the average growth of the Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (AFF) sector was a measly 2.5%, compared to the Industry and Service sectors’ average growth rates of 4.5% and 5.5%, respectively. AFF’s contribution to the gross domestic product (GDP) at constant 2018 prices declined by 37.5%, or from 15.4% in 2001 to 9.5% in 2021—with an average share of 12.8% from 2001 to 2021. It follows then that of the three major sectors of the economy, AFF’s contribution to the country’s economic growth was the smallest. Out of the 4.8% average GDP annual growth within the generation studied, the AFF sector contributed only 0.3%. For the same period, the share of the Industry and Service sectors to GDP growth were 1.4 and 3.1 percentage points, respectively.

Reflecting the very low labor productivity in the agricultural sector is the fact that, while it contributes only 10% of GDP, its contribution to the labor force is 24% of the total. It used to be much higher at 37% in 2000. Labor in agriculture grew from 2000 to 2011 by 20.5%, which was equivalent to around 2 million workers. The number of agricultural workers, however, continuously decreased since 2011, during which approximately 2.3 million agricultural workers migrated to the other two sectors from 2011 to 2018. This translates to around 284,000 workers per year leaving the sector during that period, which coincided with the Philippine economy shedding its notoriety as the sick man of Asia. This period saw Philippine GDP growing at an average of 6% to 7%, one of the most rapid in East Asia. The contraction in agriculture’s employment share significantly accelerated starting 2011. From 2011 to 2018, the employment share of agriculture shrank by 10 percentage points in 2011, or from 33% in 2011 to 24% in 2018. This trend, if continued during the present Administration of President Marcos Jr., may actually favor the increased mechanization of farming, leading to an improvement of agricultural productivity. For this to happen, efforts in agrarian reform should shift from further fragmentation of land to consolidation of small farms into larger units through farmers’ cooperatives or the nucleus estate system perfected by the Malaysians in palm oil and rubber plantations.

Considering the slow growth of the AFF sector and its modest share in GDP, coupled with its relatively high contribution to total employment, its development significantly lagged behind the other sectors as measured by labor productivity. AFF’s output per work was consistently the lowest among the major sectors from 2000 to 2018, the real golden age of the Philippine economy shared by the two Presidents, i.e., Benigno Aquino III and Rodrigo Duterte. The highest productivity was seen in the manufacturing sector in which the industry’s output share was approximately 30%, despite accounting only for 16% of the total employment.

Two obvious means of increasing labor productivity in agriculture are the introduction of more capital investments and the upskilling and retooling of farmers, especially among the younger ones. The average age of a Filipino farmer is already close to 60 years. There must be a way of attracting the young, whether or not children of farmers themselves, to the vocation of a farmer and eventually the whole sector of agribusiness, which comprises not only farming but the whole value chain, from post-harvest, to storage and warehousing, processing, wholesale and retail.

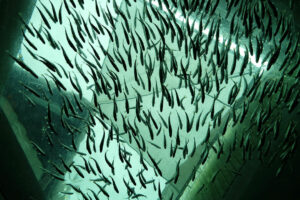

It was not only in labor productivity that the Philippine AFF sector fared very poorly in comparison to its Southeast Asian peers. The sector was weak in terms of productivity, per capita volume, and high costs (low returns) compared to neighboring countries in the ASEAN. The Philippine total factor productivity growth in AFF, which is a measure of productive efficiency, was the lowest in 2010 to 2014. Subsequently, average farm yield in the Philippines was 9% and 67% lower than in Malaysia and Vietnam in 2014, respectively. This low productivity of the Philippine AFF sector in great contrast with Vietnam is one major explanation why Vietnam surpassed us in per capita income in 2020. What Vietnam has accomplished in reaching high levels of productivity in rice, coffee, and aquaculture should be emulated by the Administration of President Marcos Jr.

Philippine manufacturing, both for the domestic and foreign markets, can be given a big boost if we can improve the forward linkages of the AFF sector. Unfortunately, these linkages are weak in comparison also to our ASEAN neighbors, especially Thailand that is considered the agribusiness behemoth of Southeast Asia. The forward linkages of the Philippine AFF sector to manufacturing grew marginally by only 10% from 1994 to 2012. In contrast, the contribution of food and beverage (the likes of San Miguel Corp., Robina, Century Canning, Monde Nissin, etc.), which largely depend on agricultural or aquacultural products for inputs, to total gross value added (GVA) of manufacturing grew very rapidly during the 2000 to 2021 period. The share of food and beverage manufacturing to total GVA of the manufacturing sector (one of the major components of industry) rose from 36% in 2001 to a whopping 55% in 2021.

Given the meager forward linkage of the AFF sector, this implies that the food and beverage manufacturing subsector relies heavily on imports for its inputs. It stood to reason that agri-food exports of the Philippines were, on average, around three times and six times less than Vietnam and Thailand, respectively from 2001 to 2020. Philippine agricultural trade deficits were likewise widening. International trade economist Ramon Clarete estimated that the Philippines incurred large potential export income losses of approximately $230 million in 2018 alone.

Needless to say, the low productivity and the diminishing competitive advantage of the Philippine AFF sector have two primary negative impacts on sustainable and inclusive growth: low wages resulting in high poverty incidence among agricultural workers, and soaring domestic prices, which were exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. Given the relatively low productivity of labor in agriculture, wages in the sector are expected to be lower than those in industry and services. True enough, the average daily basic pay in agriculture, at constant 2006 prices, was approximately 55% and 46% lower than in services and manufacturing, respectively, in 2016.

The most tragic consequence of the low productivity of the AFF sector is mass poverty in the rural areas, where three-fourths of Filipinos falling below the poverty line are. Agricultural households had poverty incidence approximately four times higher than non-agricultural households from 2003 to 2015. On the other hand, although visibly underemployed workers accounted only for 12% of total workers, the rate of poverty among visibly underemployed in workers in general was at 34.2% while poverty incidence of visibly underemployed agricultural workers was at 44% in 2015.

Finally, the backwardness of the AFF sector resulted in high domestic food prices, contributing to malnutrition and ultimately to lesser and/or slower human development of poor households.

The average share of food and non-alcoholic beverage to headline inflation was significant at 43% from 2000 to 2021, with 57% being accounted for by the other 10 major commodity groups. Given that the poorest of the poor households spend approximately 60% of their total income on food items, rising food prices inevitably lead to higher incidence of malnutrition. This was exacerbated during the pandemic. Malnutrition is significantly higher in the Philippines compared with its ASEAN peers. In 2018, malnutrition in the Philippines, especially among children, is nine times, 20 times, and a whopping 287 times compared with that of Thailand, Malaysia, and Vietnam, respectively. This state of affairs in the area of food security has very tragic consequences on the quality of our human resources.

(To be continued.)

Bernardo M. Villegas has a Ph.D. in Economics from Harvard, is professor emeritus at the University of Asia and the Pacific, and a visiting professor at the IESE Business School in Barcelona, Spain. He was a member of the 1986 Constitutional Commission.