Financial system is both institutions and markets

We have no doubt that the off-cycle, huge policy rate adjustment by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) last month continues to surprise both market analysts and economists. In a positive way, many of them admit that such a single move re-anchored inflation expectations and minimized the peso exchange rate’s volatility. Yet many incurable growth proponents maintain that such monetary tightening could compromise economic recovery by restricting business activities via the banks’ lending operations.

But four years ago, two senior economists from the BSP’s Department of Economic Research (DER), Carolina P. Austria and Bernadette Marie M. Bondoc (“The Impact of Monetary Policy on Bank Lending Activity in the Philippines,” 2018) had already found very weak to no evidence of monetary policy transmission through the Philippine banks’ lending channel. They used the Kashyap and Stein model that posits the idea “that banks cannot frictionlessly tap uninsured sources of funds to make up for a central bank-induced shortfall in insured deposits.”

This proposition implies that monetary policy affects banks in various ways. Those with adequate liquidity, for instance, could reduce their securities holdings to maintain their level of credit operations. For those with limited liquidity, loans may indeed have to be reduced if the securities level is low.

The Austria-Bondoc research was significant from the perspective of the BSP itself because its own in-house research activities had yielded mixed results on the existence and strength of both interest rate and bank lending channels of monetary policy. One paper done in 2008 found that with the shift to flexible inflation targeting (FIT) in 2002, the expectations channel has assumed greater importance in transmitting monetary policy in the Philippines while the interest rate channel has weakened. Both the credit channel and asset price channel remain closely linked because of the dominance of banks in the financial system.

Other research found that FIT has actually strengthened both the interest rate and bank lending channels although the transmission remains relatively weak considering our shallow financial markets. The BSP was found to have retained the capacity to influence market interest rates through the adjustment of the policy rate. A focused study on the bank lending channel also supported both its existence and magnitude.

But using a greater sample size and covering a longer period compared to previous BSP studies, with a number of robustness checks by varying bank groupings, policy rate used, and removing foreign banks from the sample, Austria and Bondoc, to reiterate, failed to see strong evidence of monetary policy transmission through the bank lending channel.

The BSP’s senior economists’ explanation is robust:

1. Banks rebalance their loan portfolio instead of actually shrinking it. This is consistent with other empirical results showing that monetary policy tightening could have the immediate impact on real estate and consumer loans but commercial and industrial loans do not necessarily have to adjust.

2. Well-capitalized banks, as in the Philippines, could de-link their lending operations from monetary policy shocks like a policy rate adjustment. Banks have become risk-conscious in their credit operations as the quality of loans remained stable. This means that even in credit booms, banks could always choose to lend discriminately. One proof is that despite the economic lockdown, nonperforming loans continued to be relatively low.

3. Financial market liberalization in the Philippines in the 1990s has weakened the ability of bank lending to reflect monetary policy stance. Proliferation in bank loan alternatives, financial market deregulation, and increase in securities trading have all weakened the link between the real economy and the bank lending channel. The weakening of this monetary policy transmission mechanism actually motivated the BSP in establishing the interest rate corridor system.

4. BSP regulations impose hefty penalties for banks mixing up funds in the regular and foreign currency deposits. External liquidity could only affect domestic lending if the BSP purchases those proceeds in the market.

5. The period 2008-2015 could be abnormal because of unorthodox monetary policies in the major economies. Since the upsurge in capital led to an extraordinary rise in monetary growth, the contractionary monetary policy could have been more than swamped by the expansionary impact of those capital flows.

Austria and Bondoc were correct that the main challenge to the monetary authorities is to ensure “that tools, including policy rate, reserve requirements, auction volumes for deposit facilities, and macroprudential measures are used in concert to effectively transmit monetary policy to the economy.” Monetary policymakers can always leverage on various channels of monetary policy, establish good coordination between monetary policy and operations, and employ macroprudential measures to influence bank lending behavior.

Which brings us to another excellent working paper from the BSP that was just released last month entitled “Introducing a multi-dimensional financial development index for the Philippines” by Jean Christine A. Armas and Nerissa D. De Guzman, both senior economists from the BSP’s DER.

What is interesting about this working paper is that it clarifies this nexus between the financial system and economic growth. Economic growth is driven by an efficient saving-investment channel, productive capital, and technological innovation. These growth-positive channels are optimized when the financial system is well developed. But therein lies the rub — we would normally equate financial development only with private sector credit to GDP and, to some extent, stock market capitalization. Or in other words, when we assess the impact of monetary policy tightening, for instance, we only have in mind the bank lending channel of monetary policy. Ergo, high interest rates erode economic growth and therefore, the BSP should go slow in navigating the trade-off between growth and inflation.

Following Armas and De Guzman, we can argue that limiting the assessment to credit and stock market implications of a monetary action would only capture the depth of the financial system. What they offered in their working paper is a multi-dimensional index that measures the level of development in both the system’s institutions and markets in terms of access, depth, efficiency, and stability. The BSP senior economists therefore improved and extended the index originally constructed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 2016.

This enhancement is very useful because of the dramatic evolution of financial systems across the world and in its wake, has also spilled over to those of the emerging markets including the Philippines. While banks continue to dominate the financial system, it is necessary to consider the growing importance of non-banks, particularly private insurance corporations. Future research will have to cover the other financial corporations on which data series began only in the first quarter of 2017.

Elsewhere in their paper, the BSP senior economists also made the point that “large amounts of credit provision do not necessarily correspond to broad access to and efficient delivery of financial services…” We need to go beyond one single dimension of the financial system, or just the financial institutions alone.

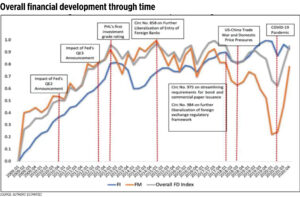

Looking at the financial developments in both the financial institutions (FI) and financial markets (FM) in the Philippines in all the four metrics of access, depth, efficiency, and stability and the singular index (Overall FD Index) would show that the Philippine financial system “has progressed and developed quite remarkably.”

As this chart shows, both external developments (for instance, US Federal Reserve quantitative easing in 2010, 2012; US-China trade tension in 2018; COVID-19 pandemic in 2020) and key domestic regulatory and policy reforms (for instance, on financial access and inclusion in 2014 and 2018, monetary policy normalization in 2014) drive the system’s access, depth, efficiency, and stability.

Armas and De Guzman’s paper is very significant because it proves that focusing only on financial institutions, as most of us do today, would ignore the other plank which is the financial markets, as well as key financial dimensions other than depth. On the other hand, Austria and Bondoc alerted us on the need to consider different channels of monetary policy transmission other than the usual bank lending channel in assessing the impact of monetary action, for instance. Otherwise, we might be missing many points.

This is how we transport an elephant in the room.

Diwa C. Guinigundo is the former deputy governor for the Monetary and Economics Sector, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). He served the BSP for 41 years. In 2001-2003, he was alternate executive director at the International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC. He is the senior pastor of the Fullness of Christ International Ministries in Mandaluyong.