Powering up an archipelago with microgrids

SOLAR PV SYSTEM – Lahuy Island – Camarines Sur Qualified Third Party Project — FP ISLAND

By Martin Antonio A. Lacdao, FP Island Energy Corp.

A QUICK SEARCH on the internet for “Philippine map at night” will invariably return satellite images showing the country lit up by evening lights. It’s easy to spot the National Capital Region and neighboring areas since they appear as a glowing streak stretching from Pampanga in the north to Batangas in the south. Metro Manila, at the center, shines with a fierce intensity which reflects the population density and electricity use in the area

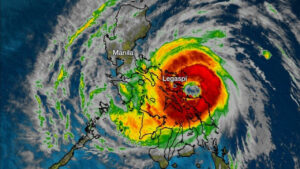

It’s also not hard to pick out the glowing lights of the country’s major urban centers such as Metro Cebu, Iloilo City, Bacolod, Cagayan de Oro, Iligan, Zamboanga City, General Santos City, and Metro Davao. A person keen on geography can make a quick game of picking out individual towns and cities like Baguio, Laoag, Legazpi, Puerto Princesa, and even Busuanga in Coron. However, as fascinating as this game may be, attention is inevitably drawn to the dark spaces in between.

There are large swathes of the Cordilleras, Cagayan Valley, South Cotabato and Sultan Kudarat where there is not even one pin-prick of light. The darkness gets even more pronounced in the island provinces where there may be just one point of light showing a large town. While this information may be of some general interest to the casual observer, for those involved in the task of rural electrification, these maps of the country at night are a reminder of what still needs to be done.

According to the Department of Energy (DoE), in 2021, 93% of all Filipino households have access to electricity. This, however, obscures the fact that access to electricity does not necessarily mean getting it 24/7. In most rural areas, especially in islands, electricity service is limited to four to eight hours a day. In a perfect world, all the households in the country would have full-time access to electricity. But, through the years, this goal has remained elusive. One factor making this goal difficult to achieve is that the Philippines is an archipelago of 7,641 islands, and it is simply more difficult and costly to supply electricity to islands.

Electrification starts in the huge population centers of the mainland where power generation plants are built. By putting up transmission and distribution lines, the electricity generated from the power plant can be supplied to consumers. For as long as the transmission and distribution lines can reach a town or village, the consumers there are considered “on the grid.”

A problem occurs, however, when the transmission lines hit water’s edge on the main islands. At that point, a choice has to be made on how to power up islands off the coast.

One option is to extend a transmission line to the island by laying a submarine cable. In this manner, the power generated on the mainland is sent to the island, bringing the consumers there “on the grid.” This solution, however, is expensive, since laying down cable and building the associated infrastructure costs a minimum of P170 million per kilometer. Since these costs mount the further away an island is from one of the main islands, laying down submarine cable is usually reserved for connecting major islands with huge populations and robust economic activity. An example of this is the interconnection of the Luzon Grid with the Visayas Grid through an undersea cable between Bicol and Samar.

However, for roughly the same cost of laying down a kilometer of submarine cable, a small power generation plant and distribution system can be built on an island. Since the transmission line from the mainland is not extended, the island is considered “off-grid.”

Because of the high costs associated with undersea cable, building these small electricity systems has become the preferred mode of powering up smaller and more distant islands. These off-grid islands are also called missionary areas, and the task of providing power to them has principally fallen to the National Power Corp., (NPC), which is the country’s power generator of last resort. In these off-grid missionary areas, NPC operates the power generation plants while the local electric cooperative takes charge of distributing power to the residents.

While NPC does its best to bring power to off-grid areas, it still has to overcome a number of challenges. Until very recently, NPC powered off-grid islands using diesel-powered generators. Because of the high cost of diesel fuel, electricity in off-grid islands is very expensive and electricity service is limited to only a few hours each night.

In order to spread the burden of providing electricity in off-grid areas, the Electric Power Industry Reform Act (EPIRA) allowed the private sector to supply power in remote and unviable areas through the Qualified Third Party (QTP) program. Through the QTP program, private companies which had the required technical, legal and financial qualifications were allowed to generate and distribute power in rural and off-grid areas on the condition that they supply 24/7 power. Under this program, a private company would replace both the NPC and the electric cooperative as power generator and distribution utility, respectively.

Since the passage of EPIRA in 2001, QTP projects have been established in off-grid areas in Palawan, Cebu, and Camarines Sur. However, despite the best efforts of the DoE to roll out the QTP program, as of the end of 2021, only 11 QTP projects had been awarded.

In the early years of the QTP program, private developers also used diesel-powered generators to supply power in off-grid islands. However, in the last five years, technological improvements such as the rise of microgrids and the development of smart microgrid controllers paved the way for a resurgence in the QTP program and led to the use of renewable energy (RE) as a source of power.

In its simplest terms, a microgrid is a power generation and distribution system that supplies power to a defined geographical area such as a township, an industrial park, a military base, or a small island. Because it has its own generation and distribution facilities, a microgrid is capable of operating independently of the main power grid and, thus, is capable of supplying power in off-grid areas.

In more advanced microgrid systems, a smart microgrid controller is used in order to seamlessly orchestrate the supply of electricity coming from various power sources. This is crucial in case the microgrid is powered by RE sources such as wind, hydro, or solar power. While RE sources provide clean energy, they are intermittent by nature (e.g., a passing cloud can disrupt solar power production). Thus, a smart microgrid controller is used to ensure a smooth transition between the various RE sources so that consumers enjoy uninterrupted power. Microgrids that use smart microgrid controllers are called “smart microgrids” and are fully capable of supplying 24/7 power to off-grid areas using RE sources.

Because of the advantages of using smart microgrids in off-grid areas, the Microgrid Systems Act (MSA) was signed in January 2022. While the MSA built upon the foundations of the old QTP program, it was a more streamlined version with accelerated timelines for the competitive selection process (CSP) and project execution.

An essential feature of the MSA is that it included well-defined criteria for determining unserved and underserved areas (that is, areas with less than 24 hours of electricity). Once an off-grid island is determined to be unserved or underserved, the DoE can initiate a competitive selection process to choose a microgrid service provider that will provide 24/7 power to the island.

Furthermore, unlike the old QTP program, which was open only to private corporations, the MSA broadened the field of microgrid service providers to include private corporations, local government units (LGUs), cooperatives, nongovernment organizations, generation companies, and distribution utilities.

With the recent issuance of the implementing rules and regulations of the MSA, microgrid developers such as FP Island Energy Corp. (FP Island) are eagerly awaiting the start of the CSP process which will kick off once the DoE publishes the initial list of unserved and underserved areas. If this list is issued within the year, the selection process can start soon after and more residents in off-grid islands can look forward to having 24/7 power as early as the middle of 2024.

For its part, FP Island hopes to build on the initial success of its microgrid project in the islands of Lahuy, Haponan, and Quinalasag in Camarines Sur. Prior to the start of FP Island’s commercial operations in December 2021, these islands received a maximum of 12 hours of electricity daily. By using a hybrid generation system which combined an RE source (solar power and battery storage) with conventional energy sources, FP Island has been providing 24/7 power to more than 2,200 households in the islands. FP Island uses a smart microgrid controller to ensure that power is supplied mainly by RE sources. In fact, in Haponan Island, solar and battery power supply almost 100% of the electricity needs of the residents.

While the smart microgrids in the islands have been operating for a little more than six months, life on the islands is already changing. From the purchase of more durable appliances like refrigerators and electric stoves to the establishment of small businesses like “bayad centers” and ice-making facilities, the lifestyle and economic prospects of the residents are looking up. Significantly, a lot of new houses are being built because people are moving back from the mainland because of the availability of 24/7 electricity. There is a renewed sense of optimism in the islands and it is this feeling of empowerment that FP Island would like to replicate in other off-grid islands in the country.

Through its microgrids, FP Island hopes to add more pinpoints of light to the “Philippine map at night” to reduce the areas of darkness, especially in the outlying and off-grid parts of the archipelago.

Martin Antonio A. Lacdao is the business development officer of FP Island Energy Corp., a wholly owned subsidiary of First Philippine Holdings Corp., which develops and operates smart microgrids in off-grid islands, industrial parks, townships, and resorts. He can be reached at malacdao@fpiec.com.ph.