Russian invasion of Ukraine or not, world oil prices are going up

As the world’s economy is recovering from its two-year COVID-19-induced slump, it gets hit with another crisis apparently from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Brent crude oil price spiked to $105 a barrel, says guardian.com. Eastern Europe has apparently replaced the Middle East as the world’s cauldron where energy price volatility is heated up.

But even before Putin’s tanks crossed Ukraine’s border, oil prices had already simmered up by $20 a barrel since the start of 2022.

The current market disturbance in fuel markets apparently suggests a reconfiguration of the fuel trade, bringing the world’s energy market to uncertain equilibrium with high oil prices. The present price instability appears to reflect three tensions in fuel markets. One, as the world economy wakes up from its two-year hiatus because of the COVID pandemic, its increased demand for oil has not been matched with adequate supplies of oil and gas. The expansion of 400,000 barrels per day by OPEC countries and Russia is significantly less than the oil demand requirements of global economic recovery.

The supply and demand imbalance reflects the second problem: the alliance of OPEC and Russia. OPEC is an organization of 13 of the world’s oil producers, most of whom are in the Middle East and Africa. The coalition reminds the world of the OPEC oil price hikes in the 1970s, except this time, it appears worse as half of the world’s oil supply is controlled by an apparently more powerful oil cartel.

Thirdly, the US could countervail cartelized oil prices, but it chose not to because the Biden administration appears committed to the environmental woke cause to wipe out the carbon footprint in our planet in the soonest possible time. The pressure to replace fossil fuel is getting stronger, which downplays investments in coal mining and oil drilling. Even the cleanest of fossil fuels, natural gas, must go if the climate change activists would set the rules.

Hesitancy prevails among US energy producers, a great difference from the Trump administration six years ago. While higher oil prices could have automatically triggered new investments in oil drilling and natural gas fracking and refining in the past years, policy and regulatory uncertainty weakens the Biden administration’s capacity of persuading US oil and gas producers to produce more.

The Keystone XL pipeline of natural gas from Canada to the US was opposed by former President Barak Obama, strongly encouraged by former President Donald Trump, and was cancelled by the current administration. To please its climate change base, the Biden government issued executive orders to slow down oil drilling and gas fracking.

Thus, the short run capacity of the US to offset price setting by Russia and OPEC is weak, and its medium- to long-term capacity is not there as well. The Keystone pipeline could have delivered 900,000 barrels per day of crude oil from Canada to the US refineries, easing oil price inflation in the world today.

The problem is that the pressure to shift to cleaner renewable energy is just getting stronger each year because of climate change itself, but the world is not ready yet in the short run for the substitution which has to take place. We observe this pressure as well here in our country, with cleaner fuel advocates pressuring the Department of Energy to stop issuing approvals for coal fired plants.

At present, efficient storage of renewable clean energy is not available yet to address the intermittency problem of renewables, at least not in the scale for the world to significantly de-carbonize its energy use in the next 10 years.

Natural gas is a realistic intermediate step from coal or diesel to renewable energy, or, if not that, a combination of gas and clean energy. To do this, countries would have to invest in capital intensive facilities to liquify the gas for the efficient transport of it across the world, and re-gasifying it to be processed into energy. Importing and exporting countries are making these investments, but not fast enough to address the short run problem of the mismatch between oil supplies and demand, thanks to OPEC and Russia.

This hesitancy is fueled by the uncertainty about the future of gas fracking in the largest gas supplier in the world, the US. The extreme right wing of climate change activism is uncompromising in its position against strengthening an industry built around this less dirty energy source, natural gas. The current Biden administration is bending to the pressure, and ordered the slowing down of gas fracking. That fans the hesitancy of investors to expand liquified natural gas (LNG) facilities not only in importing countries, but also in the US itself. If there is less gas to liquify and export, US investors would not risk capital in building more gas liquefaction plants and expensive LNG carriers. If there is less gas to import, importing countries would tend not to invest in more LNG-fueled power generation capacities.

With its narrow trade highway and remaining so in the longer term given the politics in the US, natural gas is not a viable tool in offsetting cartelized oil prices by OPEC and Russia. The problem about this trade highway is its high specificity to LNG. It has only one use, which is to transport LNG, unlike other trade highways which are truly public facilities serving several industries. This highway is just like the 500-kilometer pipeline connecting Malampaya near Palawan to Batangas. When the Malampaya gas runs out, there is no other use for it until the country discovers a new gas reserve in the vicinity.

For the same cause of cleaning our planet of carbon emissions in the atmosphere now, investments in new oil supplies are being held back or may never be made. Thus, the world may be entering a regime of high oil prices with the new normal price exceeding $100 a barrel.

World oil prices would still go up, even if Russia did not invade Ukraine. If the current war in Eastern Europe is not a primary contributor to the upward calibration of oil prices, what triggered it? It is the global economic recovery, and the world’s stronger resolve in fighting climate change. While the global demand for energy rises, oil suppliers are holding back supplies, and the renewable energy cum natural gas compromise is not a viable option to neutralize OPEC and Russia’s control of oil prices.

Oil prices may go down with possible changes in the world in the medium term. First, if the Biden administration changes policy and encourage natural gas fracking and investments in LNG facilities, then energy deficit countries invest in the LNG trade highway and in LNG-using power generation capacities. These can be done in less than five years. Of particular interest is developing the LNG trade highway between the US and East Asia.

Secondly, if scientists and engineers develop an efficient storage technology for renewable power, one that elevates renewables to become a reliable 24/7 source of power for the world. This option is, however, not yet apparently feasible in the next 10 years.

Thirdly, if the experts refine the concept of combining gas and renewables, which promises to be a more realistic plan to accomplish in the medium term. This requires the understanding and cooperation of climate change advocates to allow authorities to adjust their policies and regulations and encourage private sector investments in both LNG and renewables. In any of the above three scenarios, the control of OPEC and Russia over oil supplies is weakened by the rise of renewables and LNG.

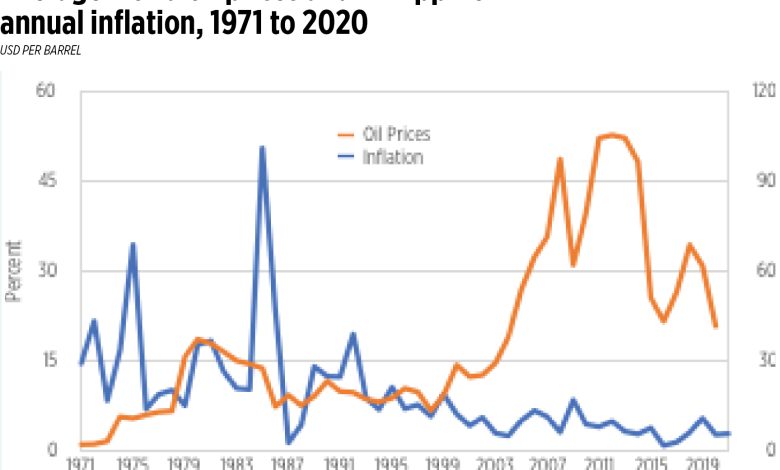

How does this present situation affect our country’s economic situation? The impact of the current oil price spike is already felt in the country with rising local fuel prices at the pump. Consumer prices are expected to be pushed up by it, but can still be kept within the target range of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) of 2% to 4%. Since the start of this millennium, average crude oil prices have significantly been on a rising trend but monetary authorities have somehow kept annual inflation rates within target 60% of the time (see the chart). In the years that inflation breached 4%, the country experienced other supply chain disturbances for food items such as the rice price spike in 2008 and 2018.

About one and a half months ago, BSP Governor Benjamin Diokno said the country can meet the target inflation range of 2% to 4%, based on crude oil prices holding at below $95 a barrel. Given oil prices this month, BSP’s inflation forecasts for this year and next may have to be adjusted upwards.

Ramon L. Clarete is a professor at the University of the Philippines School of Economics.