Sugartime is anytime?*

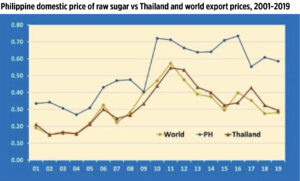

If there’s one chart that captures what ails the Philippine economy today, it must be this one from the National Economic and Development Authority’s (NEDA) “An Assessment of Reform Directions for the Philippine Sugar Industry” published in 2021.

Unlike sugar prices in Thailand which mimic world sugar prices, sugar prices in the Philippines have been phenomenally higher in the last 20 years — an outlier. Note that Thailand is now the second largest sugar producer next to Brazil, but in the Philippines, it’s more talk than anything else. For instance, in 2020, the Sugar Regulatory Administration (SRA) announced it would conduct a benchmarking analysis in Thailand to enable it to extract the most appropriate processes for local application. At most, a committee was formed to push the competitiveness and advancement of the local sugarcane industry.

But four years earlier, in 2016, the SRA also announced that it was “looking at adopting technological advancements in agriculture from Thailand to boost sugarcane productivity in the Philippines.” A technical team from SRA was sent to Bangkok to do “technology and policy scoping and benchmarking analysis.” The team met with agricultural academics and practitioners to discuss agricultural feed stocks for energy production and waste water management, and checked feedback from farmers who bought Thai farm machinery and equipment for possible use in the Philippines.

Whatever happened to these brave attempts escapes us because until recently, the Philippines continued to suffer from low sugar yield, estimated a couple of years ago at 5.1 tons sugar per hectare, something that pales in comparison with other sugar-producing countries like Columbia with a yield that is 2.38 times higher; Australia, 2.15 times; and Thailand, 1.22 times. In terms of sugar recovery, Brazil, Australia, and Thailand all surpassed the Philippines’ performance.

Therefore, sugar prices in the Philippines could only be much higher, as captured by the NEDA’s chart.

Annette M. Tobias of the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development also wrote as much in her earlier research, “Initiatives and Implications of Philippine Sugar Liberalization,” published in March 2020. She made that point by citing that as of November 2019, retail prices of raw sugar in the Philippines were anywhere between $0.08-$1.10 per kilo while the World Bank reported that world market prices averaged only $0.27 per kilo.

Tobias concluded: “Given the wide disparities in prices, even including transport and marketing costs, sugar in the world market could still be drastically cheaper compared domestically.” By this criterion alone, liberalizing sugar imports makes for a sensible policy.

Through good non-partisan public policy and no-nonsense implementation that defies cartels and smugglers, we should be able to address the long-term problems of the sugar industry. The SRA that controls trade and domestic supply and prices of sugar could be restructured along the reforms of the National Food Authority. Liberalization of the sugar trade will allow the importation of cheaper sugar from more efficient and higher sugar-yielding countries like Australia, Brazil, and Thailand.

True, about half of domestic sugar production is consumed by industrial users and only about a third by households, but industrial production is also oriented to domestic consumption. Cheaper sugar should benefit consumers while any proceeds from tariffication could be used to modernize the sugar industry.

Production issues are just awesome. Issues involving planting materials, soil fertility, irrigation, and effects of higher temperatures could be addressed through improvement in the varieties of planting materials, establishment of nurseries, enhanced use of fertilizer, and more efficient irrigation systems.

We don’t lack legislation either. We have the 2015 Sugarcane Industry Development Act (SIDA) mandating funding support to the industry to block farms for sugar, socialized credit, capacity building, and infrastructure support programs.

Unfortunately, as Tobias admitted in her research, “the SIDA law, though enacted in 2015, is still in its infancy stage.” Her recommendation? Fully implement the SIDA law!

But some quarters would not have any of that.

In 2019, the SRA, headed by former Agriculture Secretary Manny Piñol, insisted that SRA was the sole agency tasked “to regulate the release of imported sugar in the domestic market.” It was good that then-Budget Secretary Ben Diokno reiterated the new policy of liberalizing the sugar industry but subject to 30-40% tariff rates. Liberalizing sugar imports would reduce sugar prices while the tariff would afford some protection to the local sugar producers.

Today, we are still at it, debating whether there is sugar shortage and whether we should import from higher-yielding economies. This is not surprising because within the SRA itself, we observed some quarters subscribing to the view that “importation is just a quick fix to the problem.” Some argued against the leveling off of sugar prices to the benefit of the consumers on the ground by noting that industrial and institutional use dominate domestic consumption. Some people don’t seem to realize that the products of both industrial and institutional users are also consumed by households like bread, biscuits, and other food commodities.

Thus, the deviation of retail sugar prices from farm-gate sugar prices simply reflects the structural problems in the sugar industry. As Philippine Star columnist Jarius Bondoc wrote the other day, “sugar prices… soured consumer tastes.” Compared to its level in June 2022, refined sugar now retails at P108 a kilo, about 42% higher.

NEDA’s chart, therefore, is not just about disparate prices of sugar. It’s what makes those prices disparate.

Decades of protection accorded to the sugar industry through favored prices in the US market, for instance, disincentivized modernization and technological innovations to achieve competitiveness. Restricted importation has kept sugar prices high. We have remained a low sugar-yielding producer while the hectarage planted to sugar has also shrunk over the years, giving way to residential villages, memorial parks, and sprawling malls. Sugar milling remains limited considering that it requires huge fixed investment to service all the sugar planters in various regions.

The chart is also about politics and vested interest.

For 20 years, and even longer, we have nurtured this inflationary story to the detriment of the ordinary consumers and the cause of economic welfare. The Government should not only enable but also empower domestic industries. It’s not enough that we have been extending subsidies after subsidies, incentives after incentives to key industries even as sugar has been one of our key exports in the last 100 years. Reversing the situation is not possible if the Government is not decisive, or is too incompetent to insist on science rather than be swayed by vested interest.

It’s not good for Government to be left behind by the news. Does it need to be forced by the broadsheets’ report that local carbonated drink manufacturers Coca Cola, Pepsi Cola, and ARC (the maker of RC Cola, among others) were having difficult times with a sugar shortage before considering the last resort of importation? Yet a week earlier, no less than the President himself and his Malacañang staff denied the need for outside shipment of the sweet commodity.

The forthcoming Senate query seems to be ill advised, too. The whole issue is SRA Order No. 4 authorizing the importation of 300,000 metric tons of sugar but this was based on one, the expected shortage of sugar as early as last month; two, the authority extended to Agriculture Undersecretary Leocadio Sebastian to sign contracts, agreements, and administrative issuances; and, three, the President was reportedly agreeable to sugar importation when he was briefed by Sebastian and other DA officials, based on Philippine Star columnist Boo Chanco’s quoted source. While the Government should protect the interests of the sugar industry and the farmers, the broader interest of the consumers and manufacturers should weigh in, too.

This brings us back to the NEDA chart. Replace sugar prices with those of rice, onion, garlic, ginger, pepper, or even salt; global prices of the commodity; and commodity prices in any leading producing country, and we would have a fairly good picture of agriculture and the food industry in this country.

It should surprise no one if agriculture continues to shrink in its share of GDP. It should surprise no one either if yesterday, the Monetary Board sustained its monetary tightening mode by 50 basis points.

Inflation is the direct casualty of all this drama. Yes, sugartime is not anytime, anymore.

* With apologies to the McGuire Sisters’ “Sugartime” lyrics written by Charlie Phillips and Odis Echols in 1958.

Diwa C. Guinigundo is the former deputy governor for the Monetary and Economics Sector, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP). He served the BSP for 41 years. In 2001-2003, he was alternate executive director at the International Monetary Fund in Washington, DC. He is the senior pastor of the Fullness of Christ International Ministries in Mandaluyong.