The folly of remembering martial law on September 21

Last Wednesday, Sept. 21, hundreds of activists wearing black shirts took to the streets holding up banners condemning Ferdinand Marcos’ declaration of martial law 50 years ago and chanting “never forget, never again.” Martial law survivors took part in a “conversation express” at the Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City. They later joined the 8,000 or so people gathered in the University of the Philippines campus to pay homage to the thousands of Filipinos who were arrested, abducted, detained, tortured, or killed during the martial law period.

A parade of floats depicting issues under martial law kicked off the protest rally. Images of Filipinos who died during the period were shown. A billboard poster demonizing Ferdinand E. Marcos was also displayed. A documentary film, 11,103, which features the stories of survivors directly countering many of the false narratives peddled online, premiered on the campus. The title of the film is based on the number of human rights victims who were officially recognized by the government and who received compensation from the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth.

On the same day, a “Barikada Laban sa Historical Distortion and Disinformation” was held at the Commission on Human Rights main office in Quezon City. Journalists paid tribute to the people from the industry who risked their lives in fighting for press freedom during martial law. The National Union of Journalists of the Philippines issued this statement: “On the 50th year since the declaration of Martial Law, Filipino journalists remember those who remained loyal to the truth and who did so despite a lack of resources and at considerable risk to themselves. It is in this spirit that we stand today with them [the Mosquito Press] and with each other to join the country in saying Never Again.”

Those who participated in the protest activities last Wednesday, Sept. 21, including the survivors of martial law, did so in the belief that martial law regime began on Sept. 21, 1972. But Sept. 21, 1972 was like any ordinary weekday. Business, slowed down by continuous rain and floodwaters the past weeks, was buzzing again. Government was functioning normally. Schools were open. Newspapers were delivered to homes and sold in the streets. All broadcast stations were airing their regular programs.

On Sept. 21, 1972, democracy was vibrant and functioning magnificently. Congress and the Constitutional Convention were in animated session. Senator Benigno Aquino even delivered a privilege speech before his fellow senators, reminding them of their true role in the event martial law was imposed. In the afternoon of that day, the Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties, headed by another bitter critic of President Marcos, Senator Jose Diokno, held a huge rally, estimated between 30,000 and 50,000, denouncing the plan of the president to suppress democracy.

The next day, Sept. 22, all the daily newspapers featured the Movement’s rally. In the afternoon, Senator Aquino was guest speaker of the graduating class of the Asian Institute of Management. There were as many as 16 military officers in the school that day. They were not there to secure the school or to arrest the senator. They were there as regular students of the Master in Business Management program of the Institute.

Among them were Air Force Major Jose Comendador and Army Captain Angelo Reyes, who both belonged to the graduating class. Comendador would become Commanding General of the 2nd Air Division but joined the rebels in the December 1989 attempted coup d’état and held Mactan Air Base hostage. Reyes would become Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff but withdrew the support of the military from President Joseph Estrada during the EDSA Revolution of January 2001.

I remember distinctly that talk of Senator Aquino because I was conducting class in the room next to the lecture hall where he was sharing with the students his vision of “The Philippines after Marcos.” After his harangue against President Marcos, Dean Gabino Mendoza invited him to the Faculty Lounge. There he told us that he didn’t think Marcos would place the country under martial law, not until 1973.

From the Institute, he went to the Hilton Hotel for a meeting with other senators. There at past midnight, or in the wee hours of Sept. 23, 1972, he was arrested — at about the same time other critics of Marcos were being rounded up and media establishments shut down.

By 1 a.m., Senators Diokno and Ramon Mitra had also been arrested. Also taken into custody that early morning were newspaper editors Amando Doronilla of the Daily Mirror, Luis Mauricio of the Philippine Graphic, Teodoro Locsin, Sr. of the Philippines Free Press, Ernesto Granada of the Manila Chronicle, and columnists Maximo Soliven of the Manila Times, Luis Beltran of the Evening News, and former senator Francisco “Soc” Rodrigo who had a political commentary program in ABS-CBN.

Free Press Associate Editor Napoleon Rama and Associated Broadcasting Company TV-5 (the Manila Times TV station) anchor Jose Mari Velez, who were Constitutional Convention delegates, were also arrested as were the other outspoken delegates — Heherson Alvarez, Alejandro Lichauco, Voltaire Garcia, and Teofisto Guingona, Jr. By dawn of Sept. 23, 100 individuals were in detention centers.

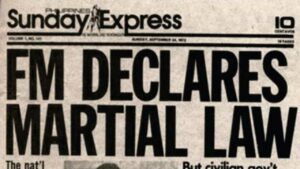

Martial law took effect in the first hour of Sept. 23, 1972 but was declared by President Marcos himself on Channel 9 of Kanlaon Broadcasting System, owned by his crony Roberto Benedicto, only at about 7 p.m. of that day.

It was only much later that Marcos said he signed Proclamation No. 1081 on Sept. 21, 1972. But on another occasion, he told a group of historians that he signed it on Sept. 17. Some say he signed it as early as Sept. 10, 1972. Others say Marcos did it on the night of Sept. 22, immediately after the staged ambush of Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile that justified the imposition of martial law in the first hour of Sept. 23.

His diary entry for Sept. 22 was, “Sec. Juan Ponce Enrile was ambushed near Wack-Wack at about 8 pm tonight. It was a good thing he was riding in his security car as a protective measure. This makes the martial law proclamation a necessity.” His entry for Sept. 25 indicated that the date of Proclamation 1081 is Sept. 23, 1972.

So, even “September 21” is a date of dubious significance. Marcos had a fetish for the numeral 7. He won over President Diosdado Macapagal by 777 votes in the presidential election of 1965. That is why he was undecided for a while between 17 and 21. The number 21 is divisible by 7, unlike 23. The numerals 2 and 3 did not add up to 7. Marcos chose 21 over 17 because September 21 coincided with the dismissal in 1939 of the Nalundasan murder charge against him.

Sept. 21 was only a product of President Marcos’ penchant for romanticizing events. Political pundits believe that Marcos wanted martial law remembered on Sept. 21 to erase from memory the events involving Senators Aquino and Diokno on that day. In 1973, he issued Proclamation 1181, designating Sept. 21 as Thanksgiving Day to coincide with the establishment of his so-called “Bagong Lipunan” or New Society.

The New Society was supposed to be similar to the “Great Leap Forward” of Mao Zedong in China and the “New Order Administration” of President Suharto in Indonesia. The apologists of the martial law regime point to the improvement of peace and order, reduction of violent urban crime, suppression of the Communist insurgency, neutralization of the Muslim separatist movement, collection of loose firearms, and instilling discipline into citizens.

The propaganda effort was so successful that is why up to the present, many Filipinos — particularly those born after September 1972 and those who were then too young to know the implications of Proclamation 1081 — labor under the misimpression that martial law was declared on Sept. 21, 1972.

As Marcos wished, people remember martial law, “the golden age,” every Sept. 21. To place significance to that date is to submit oneself to the manipulation of President Marcos’ shrewd mind. Remembering martial law on Sept. 21 is like celebrating the benevolence of President Marcos.

Remembering martial law on Sept. 23 is commemorating the beginning of “the darkest chapter in the history of post-colonial Philippines.” Remembering martial law on Sept. 23 is committing to memory the malevolence of Ferdinand E. Marcos.

Oscar P. Lagman, Jr. is a retired corporate executive, business consultant, and management professor. He has been a politicized citizen since his college days in the late 1950s.